point de vue

The first photograph in history was created by the Frenchman, Nicéphore Nièpce, in the year 1827. It was entitled “Point de Vue” and it depicted a view from the window of the photographer’s study. Monique Thomaes’ most recent video work bears this same title, one which is fraught with numerous significant meanings: first of all it means “view” or “vista”, a meaning which in principle the photograph by Nièpce also includes and which encompasses the connotations of perspective, expectation, possibility, and hope; however there is another meaning to this expression which predominates above all the others and which may be translated by “point of view”, a word carrying with it the abstract connotations of viewpoint, aspect, and angle of observation. Upon closer consideration of Monique Thomaes’ works, all these aspects and levels of meaning gain both validity and relevance. The short, repetitive sequences of the video work “Point de Vue” seem like early animated photographs; the work is visually related to such predecessors both in its color scheme as well as its lack of focus. In much the same way that the first photographic attempts using the camera obscura and asphalt coated glass plates did not allow for sharpness of definition, so within the boundaries of the monitor, do the videotape’s electronic images disintegrate into vibrating “points”.

In his book “The Basic Principals of Art History”, art historian Heinrich Woelfflin observed that throughout the history of painting and drawing the dominance of line continuously diminished; it was in this phenomenon that he maintained he was able to observe the esthetic expression of a society’s successive inner, agitated states. It is in this manner that video and computer pictures, in which there are no longer lines but rather (pixels-)points, can be seen as the provisory point of termination in this line of development. Moreover, the “nervousness” of these constantly moving and striking images serves as an appropriate symbol for the frenzied rush of our time and for the outer and inner circumstance of our culture.

However, there are other reasons why Thomaes utilizes the artistic medium of video as an instrument for presenting her ideas. One overriding reason can be summed up with a sentence written by Annelie Pohlen in her article for the catalogue “Videonale 6”: “It is above all the immaterial, the illusive, that thing which cannot be defined according to temporality, location, or spatiality, or the conceptual malleable reflection concerning, yet resisting, reality, which the technical Instrumentarium video – owing also to its connection with the flow of light energy – essentially boosts. The artist herself has indicated the above with her comment: “In this form I have attempted to reach a certain immaterialness in my themes, to allow them to become fleeting.”

Monique Thomaes emphasized the important role of “light energy” (in other words light as a formative element in her work) in another context. This question of the “form of light” – in its scientific as well as philosophical dimension – was already first broached and discussed in detailed in the 13th century essay “Forma Lucis” by the Italian theologian and philosopher Bonaventura. Light as a concrete epistemological, theoretical, abstract-religious concept has, over the centuries, repeatedly played an important role in art history – among others in the history of the painting of Flanders, the artist’s homeland.

During the years Monique Thomaes has spent in Berlin, light’s representational possibilities and the processes of perception which it requires have always played an important role in her work. Thus in view of this continuing occupation with the theme of light, one may add these diverging strands in the interpretation of “Point de Vue”: “view” as the light of hope, and “point of view” as something throwing light upon an object, thereby allowing it to appear in a new light.

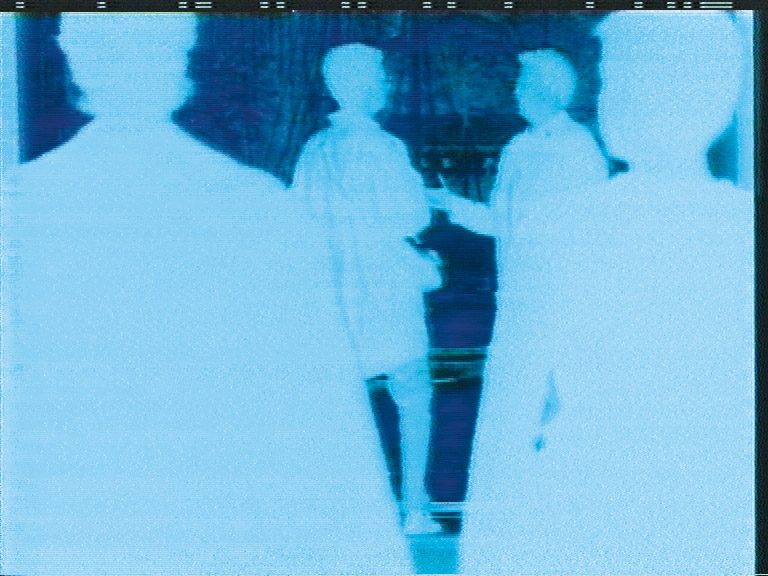

Light projections, time-light photographs, light reflections, and notes concerning light reflections were stations along the way to “Point de Vue”, a work which contains light flooded images of people appearing as though they have come from the heliotypic processes used by Nièpce. The corporeality of these figures seems to have been taken away; they express an atmosphere of brevity and transitoriness, this indeed being one of Monique Thomaes’ recurring themes.

During the shooting of their film concerning the first photograph of the world, which, as has been mentioned above, was entitled “Point de Vue – the view out the window”, Swiss film directors Bernhard Lehner and Andres Pfäffli were confronted with this “photo incunabulum” at the University of Texas in Austin, where it is kept. To their astonishment, they noticed that during observation of the almost invisible picture within the glass display case, outside of their own reflection there was almost nothing else to be seen.

The comment arising from this incident: “seeing and knowing – that which we don’t see is perhaps one of the secrets in image creation.” This statement could also stand as the motto for Monique Thomaes’ video creation “Point de Vue”.