v-ivre

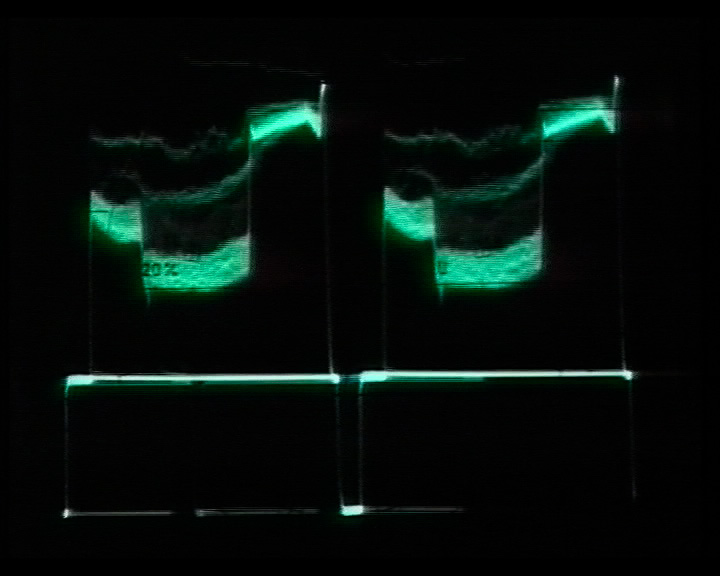

1995, 2 parts, each 10’, b/w, dv

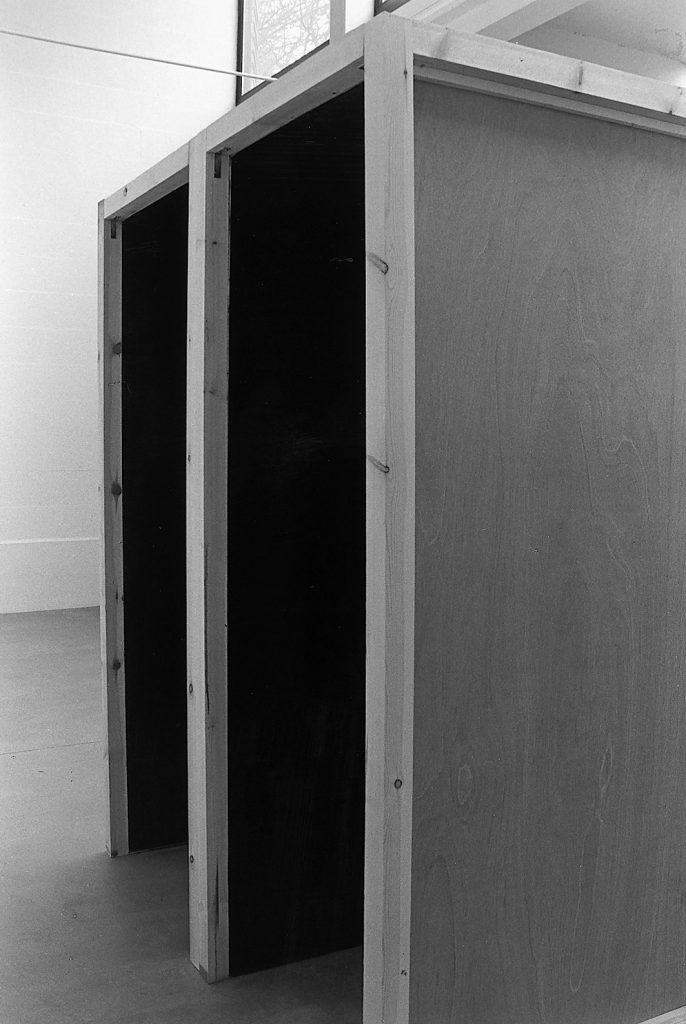

Galerie Bostoen, Kortrijk, Belgium 1996

Multimedia

Luk Lambrecht about the work

“The two ascetic videotapes show a ten minute sequence depicting inhalation and exhalation, taking place around the neck area of the artist.

The slowly moving, black and white self-portraits are, at first glance, not recognizable as such, but instead show a great similarity with abstract, three-dimensional texture. The video images are played back with a coarse grain; thereby results an aura of fundamental unfamiliarity and doubting concerning that which is perceived. Owing to effects of close-up’s, the pictures take on an incorporeal aspect and within the context of an art exhibition may be interpreted as gently rising, almost draped pictorial representations. They are forceful pictures because the observer is simultaneously aware of both video images; consequently life’s rhythm becomes distinctly conscious, an effect which is further emphasized by the occasional insertion of still-video pictures which thereby gives rise to short pauses during the run of the video.”

v-ivre

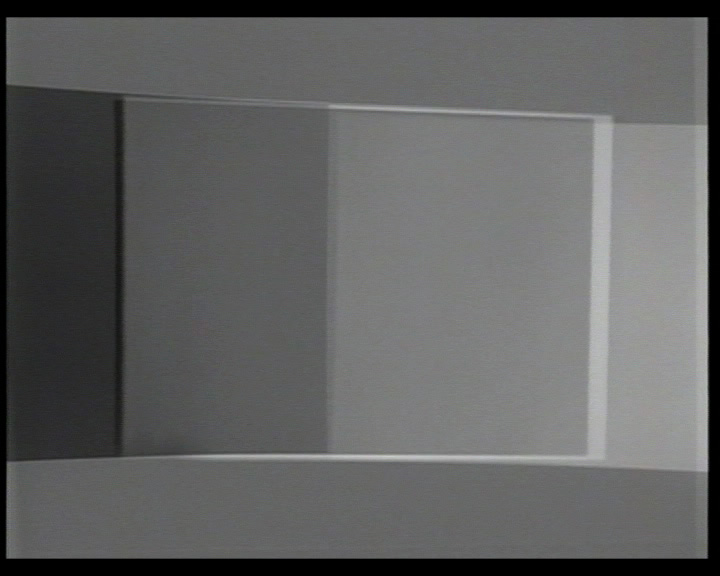

Gallery Clo Bostoen in Kortrijk-Marke is displaying the recent works of Belgian artist Monique Thomaes, now resident in Berlin. One video monitor respectively is set up in each of two minimalistic, black painted cabinets mounted next to one another. The two ascetic videotapes show a ten minute sequence depicting inhalation and exhalation, taking place around the neck area of the artist. Such a spot, usually remaining unobtrusively hidden beneath a necklace, is generally considered to be a delicate, almost mythical body part. Here I am thinking of innumerable representations throughout art history in which the unfortunate Lucretia is presented shown before she finally does herself in. In Jan Vercruysse’s 1983 photographic representation of Lucretia, the neck area became the physical focus of seduction and death.

Thomaes’ slowly moving, black and white self-portraits are, at first glance, not recognizable as such, but instead show a great similarity with abstract, three-dimensional texture. The video images are played back with a coarse grain; thereby results an aura of fundamental unfamiliarity and doubting concerning that which is perceived. Owing to effects of close-up’s, the pictures take on an incorporeal aspect and within the context of an art exhibition may be interpreted as gently rising, almost draped pictorial representations. They are forceful pictures because the observer is simultaneously aware of both video images; consequently life’s rhythm becomes distinctly conscious, an effect which is further emphasized by the occasional insertion of still-video pictures which thereby gives rise to short pauses during the run of the video. Just as the American John Coplans observed in a monitor his aging, decrepit body in order to later make split-second decisions concerning how to photograph his body, so Monique Thomaes also uses a monitor to look on during recording of a video.

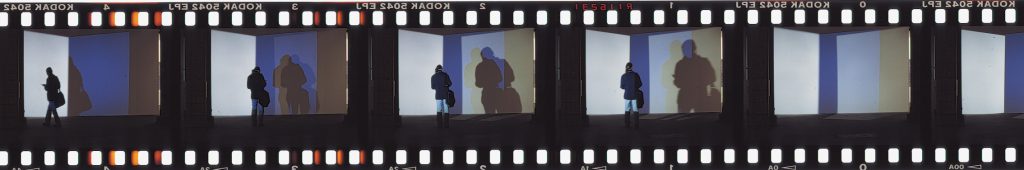

Analogous to the procedure of John Coplans, she presents in the gallery neck area photos taken from a series of 36 shots which she created based upon a precise time plan and a selection of the videos tapes. They are perfect fragments which she presents one after another like dish towels laid upon a clothing stand or like huge freely fluttering transparencies left hanging from the ceiling of a gallery’s theatrical side room.

Narrow reflective strips are attached to the wall which, owing to their suggestive height, unnoticeably reflect the visitor’s vulnerable neck area. The small reflections, the abstract video recordings, and the photos create together a kind of brief and exemplary breath-picture of present, as well as all future, visitors. In the mirrors the putative fiction of the reproductions becomes a newly fashioned ephemeral reality!

Concerning this observation, one may read in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition: “Take a step back in order to come closer to oneself. One’s own body stays back as a prototype, perhaps also as an after-image.” In its purest form Monique Thomaes presents an installation of integrity by using a simple image which, through its repetitions, takes one’s breath away.

v-ivre

Bodies become anonymous figures in her photographic and video works. Even her own body – the “pre-” picture from the video installation “V-ivre” – refrains from drawing attention to it-self and surrenders over to the granulation of the photosensitive paper. Only through cognition of the non-identical, the blank areas of representation, is identity reflected …

… forward: Two monitors, a ten minute filming sequence, uncut. Standing some distance back, both projection surfaces can be observed. Two statues. A shadow extends almost imperceptibly to the right. Darkening. The aperture contracts. The camera is close up against the body – thus when inhaling, the picture seems to edge closer, so large the minimal extension. Silently and slowly. Inhaling. Exhaling. The other picture, time deferred. Inhaling, exhaling. Another rhythm. At the same time, the same body, the same breath, unsimultaneous images. Restless breathing – fast, under pressure. The image in the monitor is black-white; i.e. gray, for the most part. Many grays. Gray like basalt. Granular like basalt stone. Rigid surface, continuous pictures. Breath on the threshold. No body. Or better: no body in the picture. No flesh, no skin. Surface, movement in time, changing volume, no location, no mass, no touching. Intimate. With what? Between whom? – De-caying. Spreading of Light. – Details – The camera before the video monitor. Picture after picture is photographed. Shudder release, dilation of aperture, shudder release. A different rhythm from the breathing in the film. Inconsiderate. In the beginning of photography one referred to the “Pencil of Nature”, that which draws upon the slides. What could be more authentic and more identical then nature’s own picture of itself? – The mirror? A fleeting picture. The mirror divides into two and yet still needs the one which finds its reflection in it. No solutions can be expected from the mirror. – Pictures with a high resolu-tion. Pictures of a relieved body. Losing itself and finding itself again. A look in the mirror. After a longish absence, I recognize myself again. – Take a step back in order to come closer to oneself. Art is abstraction for a picture. One’s own body stays back as a prototype, perhaps also as an after-image. Fear. Rigidity causes fear. De- caying causes fear. Design images of a tender transit … – always too many and always too few. Thirsty and drunken. Inhale, exhale … Repeat!