A VENIR

A VENIR – Monique Thomaes

© Stockmans en Monique Thomaes 2020

320 pages

Texte:

Monique Thomaes, Johan Pas, Angelika Stepken

Verkauf:

Stockmans, MuHKA, Monique Thomaes

ISBN 9789464363234

50 €

Angelika Stepken

Monique Tomas – L’Avenir, 2022

Monique Thomaes—L’Avenir

Monique Thomaes first discovered light as a visual material, or to put it more succinctly, as an event for her artistic work, in Berlin in the late 1980s, when her gaze not only fell upon a museum’s paintings and objects, but suddenly discovered the glass of the showcases as a kind of “time-based medium.” The mirroring effect reflected the surrounding space and visitors, while the glass surfaces became carriers of images in continuous flux.

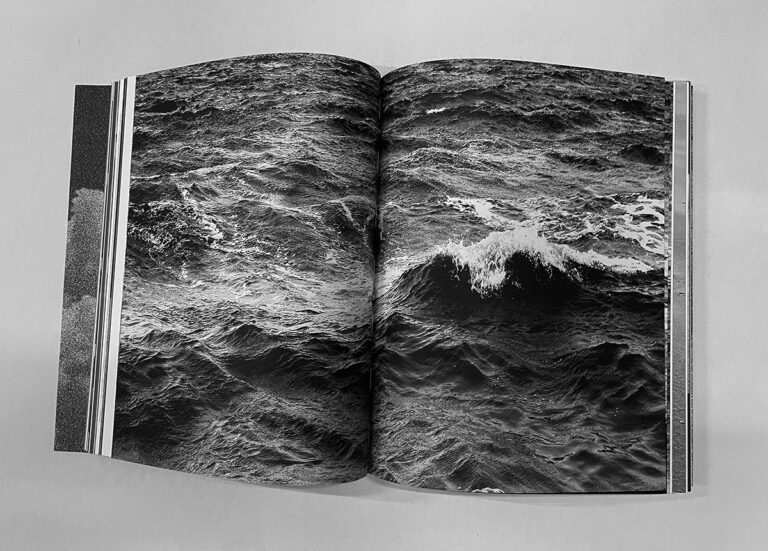

Over the next three decades, this initial “key experience” led Thomaes to her ongoing series of investigations and experiments into how light becomes visible in space, how it makes space visible, and how natural light continuously changes our spatial perception and offers an ever-shifting imagination of space. She has taken this fluidity of three-dimensional images of light and responded to and reproduced them by creating mechanical light images generated by (analogue and later digital) camera and film footage.

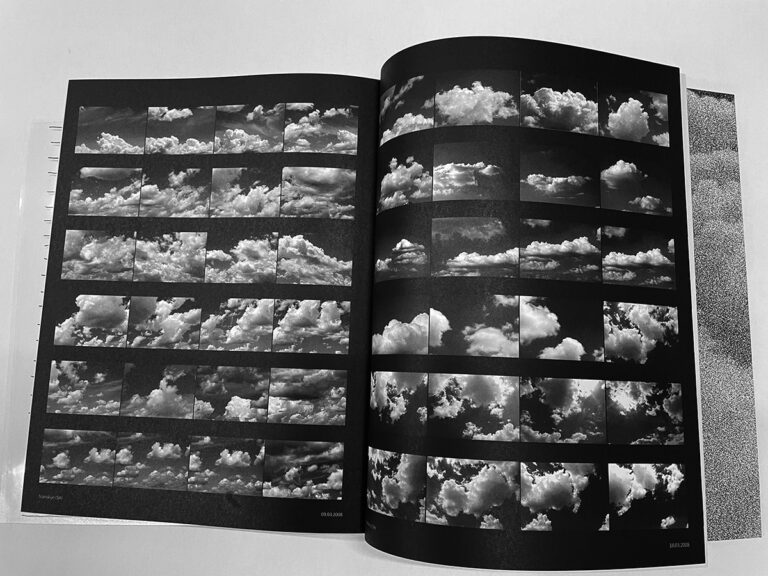

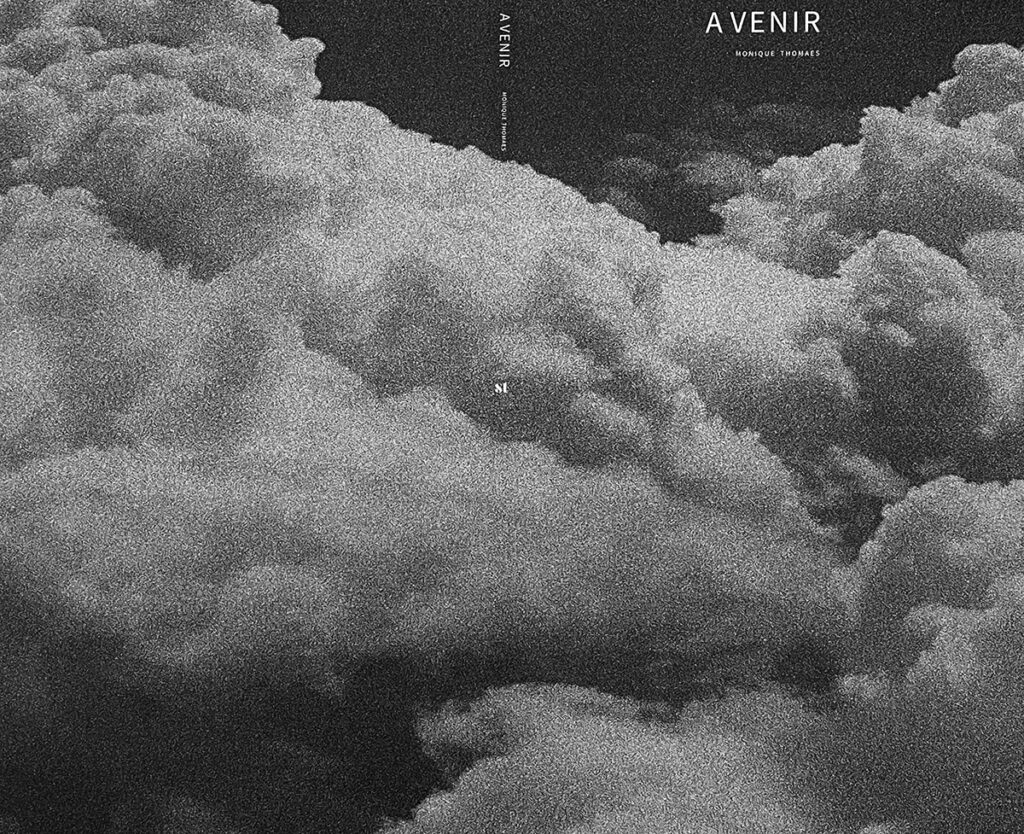

Throughout the ten years that Monique Thomaes lived in Berlin, she installed numerous light reflections in real spaces and experimented with the temporal flow of natural light, the measured time of editing, and the staccato of technical image recording. The breathing body entered the picture as slides of timed cloud images projected in the space at one-minute intervals.

Monique Thomaes has probed the boundaries of the dramatic, conflict-ridden potential in technical image production (becoming invisible when there is insufficient light, dissolving when one approaches too closely). Over the past two decades, she has concentrated on large site-specific light images (such as in 2018, at the Muze’um L in Roeselare, or 2010 at the Vrasene Chapel in Beveren-Waas), video installations (such as the permanent work in the DE MINDERE museum in St. Truiden from 2018), and the use of artificial light and light animation, as in 2010 on the facade of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp.

Time, space, and light: these are the coordinates that Monique Thomaes investigates again and again, that she manipulates and documents in her light images. While natural light can be of extended duration in real time, artificial light illuminates spaces in a static way, or casts them in shade. It is the camera’s light-giving function that gradually reveals or conceals a given space.

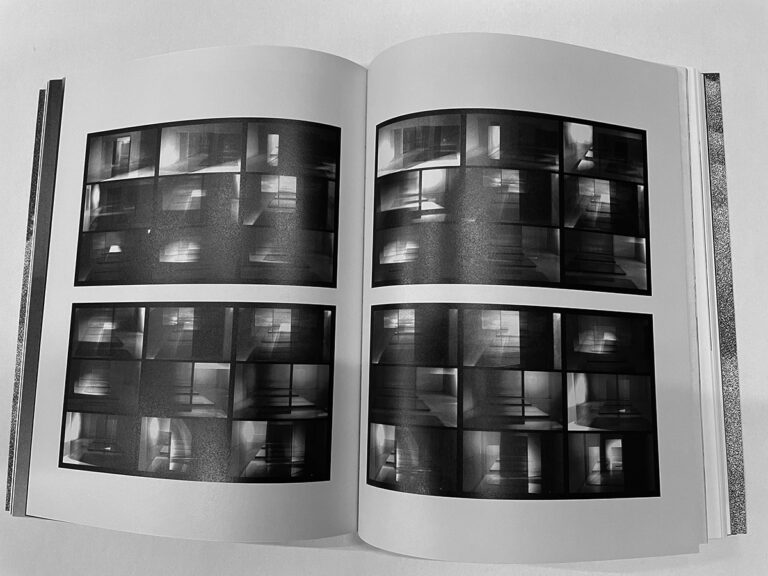

In 1995, Monique Thomaes aimed her video camera at a room in the Museum of the Celts in Salzburg-Hallein from three different positions. For eight minutes at a time, she slowly opened the camera’s aperture: what initially appeared as a narrow sliver of light in the darkness gradually expanded into a bright space that eventually became overexposed to the point that the light washed out everything that was materially visible, thus destroying the space. While light is normally understood as a medium necessary to any orientation in or perception of space, in Monique Thomaes’s work it is a powerful force that plays with the space and stages it in all its bareness. The fact that working with light in space—whether in actual rooms or their miniature models—is reflected in light-generated images (photographs and video films) is due to the storage quality of time-based media. Time is preserved, and thus becomes virtually reversible.

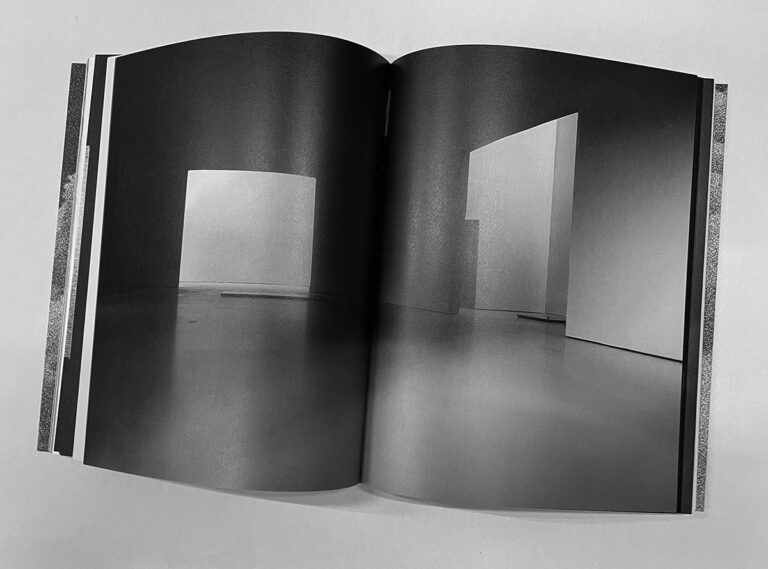

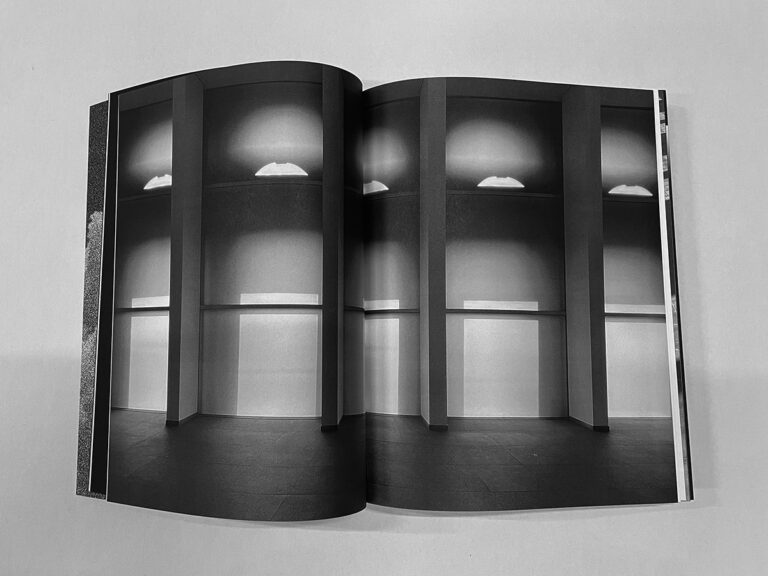

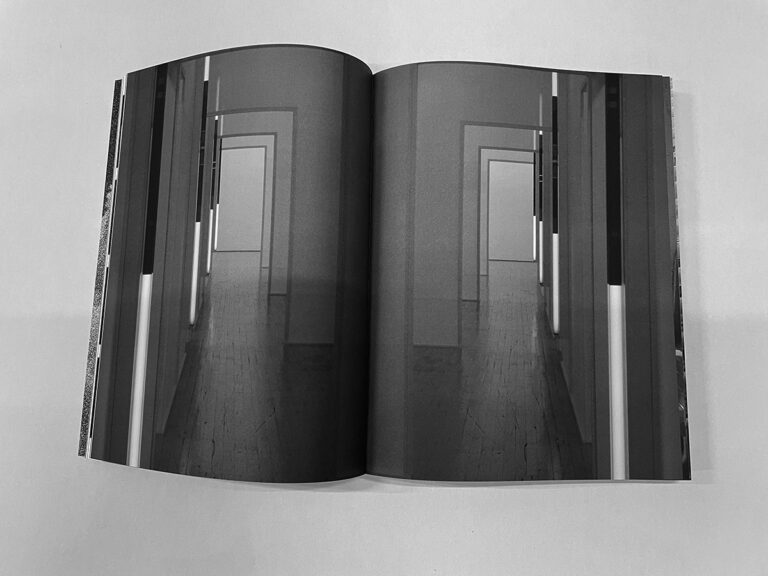

Twenty-six years later, Monique Thomaes once again turns to an empty space, or rather a sequence of spaces in the Belgian Pavilion of the Giardini in Venice and its three-part entrance area, central space crowned by a glass ceiling, and three rooms leading off to the side. Monique Thomaes built a model of the pavilion, simulated the way the light falls in from various perspectives, and used the camera to observe how the light becomes scattered throughout the space, how it refracts along edges and walls, how it reflects on the wall and floor. In all imaginable shades of light and gray, numerous digital photographs and video footage—exclusively in black and white—depict segments of rooms, perspectives, sections cropped by doorways, corners, and parts of ceilings. The black-and-white film transforms the rooms into abstract space rich with nuances of light difficult to describe. It’s a light that produces no color, but rather an immense abundance of space and image perception, an imaginary, three-dimensional, silent light theater.

How natural light becomes diffused, how it refracts and reflects in static architectural spaces is something subject to continuous change. Shifting views arise that advance toward the viewer and immerse the space in a time of “avenir,” of becoming and transforming without human intervention. Monique Thomaes takes meticulous precautions to observe this “avenir,” for instance by building detailed models of the rooms and “capturing,” i.e., documenting as many light images of them as possible. In these photographs, all sense of scale is lost.

Angelika Stepken

Florenz, 6/2022

Translation: Andrea Scrima